Fukuoka

STAY Hotel Okura Fukuoka (LUX) or WBF Tenjon Minami

DO Try and be there for the Hakata Gion Yamakasa Festival

VISIT Kushida Shrine

christina

Kyushu's largest city, and one of the most populous in Japan, Fukuoka is known as a young and happening place and is the startup city of Japan; it also has a long history as a center for trade and commerce due to it's proximity to both South Korea and China and has served as an important harbor town. We had heard great things about this dynamic place and thought to visit - little did we know how much we would love it as a mecca of culture, shopping and so much fun.

By chance, we were there for Fukuoka's oldest and most famous festival - the Hakata Gion Yamakasa, an event that dates back more than 700 years and was an amazing and inspiring sight to behold. In 1241, a Buddhist priest was carried around the city on a moveable shrine to bless the people with holy water as he prayed to relieve their suffering from a plague. The festival was born then and has evolved to include very elaborate moveable shrines called Yamakasa that are carried by teams of men, young and old, throughout the city. The event happens over the course of 2 weeks with multiple practice runs and then culminates in the Oiyama - or "passing race" - at 4:59am on the last day. The procession follows a 5km timed circuit that revolves around the Kushida Shrine - the Shinto shrine at the center of town dedicated to Amaterasu (the Goddess of the Sun and Universe) and Susanoo (the God of Sea and Storms). As a long-standing tradition, the event has been held every year since it's inception except during the World Wars and during a few years of the Meiji period, and continues to be thought to bless the city with health and prosperity.

There are 2 types of floats that are created for the festival throughout each year - Kazariyamakasa (decorated) and Kakiyamakasa (carried). The decorated floats are huge and put on display throughout the city for all to witness. Approximately 50 feet high (~16m), they are decorated by master Hakata doll makers and depict historical and legendary stories that relate to a chosen theme. These larger floats were originally the carried ones until the city's electrical wires got in the way in the late 1800s. The carried floats are still quite big at 15 feet high (~5m) and weighing about a ton.

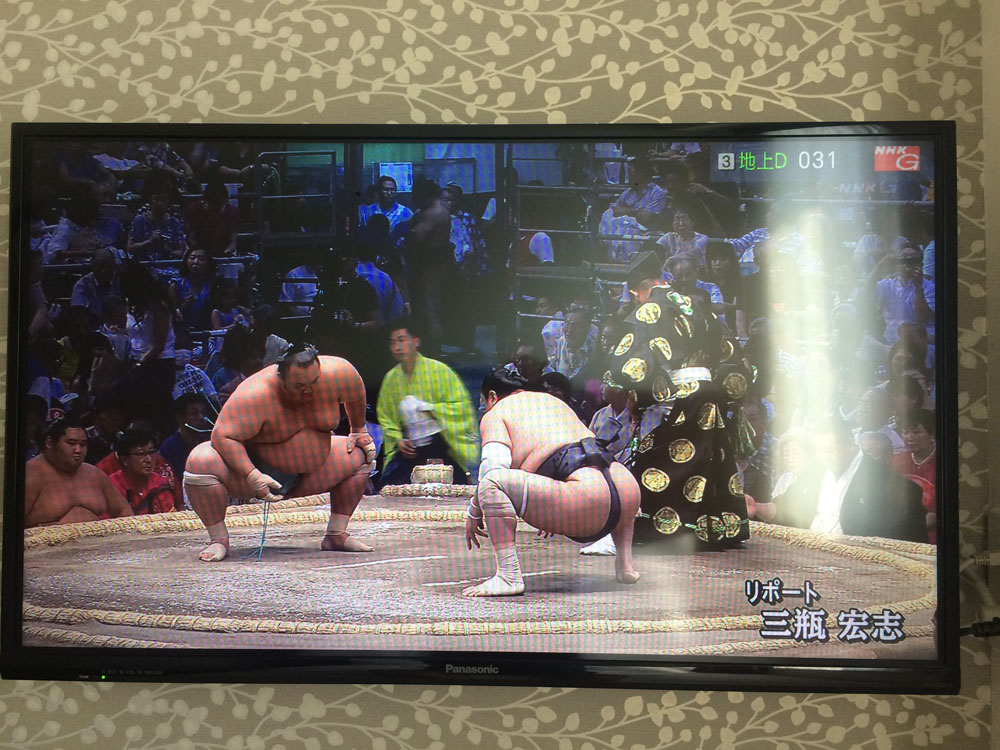

Each of the 7 neighborhoods of the city, or nagare; make up the teams that participate in the event. Within each region there are multiple ku, or districts, that come together in solidarity throughout the year to coordinate the event. Team members wear distinct uniforms of Happi coats (a short coat) with Haramaki (stomach band) and Shimekomi (loincloth). Each neighborhood or district designs their own Happi coat much like a team uniform. The proud garment is considered proper attire to wear throughout the city during the 6-week lead up and throughout the entire festival - this could be in a hotel lobby, at a convenience store or even at a wedding. The shift into this costume is considered a large part of the ritual of transformation that occurs for the participants. Colored headbands called Tenugui signify responsibility and rank of each individual - whether they be strong, a wisdom keeper or in charge of safety. The fashion is as much a part of the tradition as the floats themselves.

The intense energy as the floats pass in front of you makes the festival truly thrilling. Witnessing the last day of practice runs, it was evident how excited the teams (and the crowd) were as the floats raced through the streets and people shouted "Oisa, Oisa" (meaning, You Can Do It!). About 30 team members are actually carrying the float at one time during a 3-4 minute interval due to the amount of effort involved. Team members riding on the float, called dai-agari, are in charge of directing the intervals and bringing in fresh runners - kind of like a coach. While the people carrying the float are "on duty," the others push from the back, run out in the front, or cheer from the sides. Each person gets 3 or 4 turns as a carrier during the race. By watching the different roles being played out and how the runners change positions, you can really appreciate the amount teamwork, coordination, grace, stamina and effort involved.

Known as a rite of passage for men, the Oiyama was like nothing we have ever seen and truly charged us both to the core. It was so wonderful to witness the cooperation and community that was necessary to create and execute such a feat of human nature. What was most interesting and beautiful to watch was the inter-generational nature of this event - every boy and man from elderly seniors to toddlers were participating in this cultural expression of strength and health.

It made me truly consider the importance of ritual and tradition as a way to maintain the health and cohesion of a society. As one article I read put it, during the Yamakasa there is no societal role or hierarchy between men. Everyone is considered equal during the festival, with CEOs and janitors participating side-by-side. This reflection in the proud team uniforms along with the passed down knowledge and comradery bring unity amongst community members.

It's also worth noting that nobody keeps score! There is no record of who won but rather the event leaves a legacy of communal effort in devotion to each other and to the Gods. What a great experience to share, to witness and to learn from.